- Home

- Steve Pemberton

A Chance in the World Page 6

A Chance in the World Read online

Page 6

I looked away and resumed my habitual mask of indifference. But inside, my mind was churning. How could I find out if she was telling the truth? I turned my attention to the only person I could ask without being concerned about repercussions. “Hey, Ed,” I asked some hours later, when he and I were alone in the bedroom.

“Was my father killed, and did they have to roll a rock over his grave or something?” My tone was deliberately casual, but my heart was thumping and pounding.

“What?!” he replied. “Is that what Ma said, that Kenny Pemberton was your father?”

“I dunno,” I replied, repeating the name Pemberton silently to make sure I remembered it. “She didn’t say a name. She just said what happened to him.”

Ed looked up from tying his shoes. “Only one person died that way, and that’s Kenny Pemberton. Was one of the best boxers this city has ever seen. But he got mixed up in some bad stuff, and he got killed in some kind of fight. I don’t think he was your father, though.”

This didn’t satisfy my burgeoning curiosity. “But you’re not sure, are you? How about you ask your mother for me?” Here I reverted to my own, more distanced, way of referring to Betty, which drew a sharp glance from Ed.

“All right, but don’t get your hopes up. Kenny’s still got a lot of family around, so if you were his son, I think somebody on his side woulda told us.”

Weeks went by without Ed mentioning the boxer, and I was afraid to bring up the subject again. Then in April or May of 1978, my fifth-grade class went on a field trip to the New Bedford Public Library. Among other things, we learned how to look up old articles in the newspaper. You went to the reference desk and asked for the year during which the articles ran. They handed you a boxed spool of microfiche film, which you put in a projector. Then you scrolled through the papers for what you wanted. The task of searching interested me so much that I returned to the reference room that day during our free time. I grabbed a microfiche of old newspapers and ran them through the projector, captivated by the snapshots of the past.

I don’t know exactly when I got the idea, but soon after that visit, it sailed into my mind like a ship into port: if Kenny Pemberton was as great a fighter as Ed said he was, he would have been a big deal in the local community. The New Bedford Standard-Times, our daily paper, would have had lots of stories and even pictures about him—and definitely something about his murder. If I could just look at a picture of him, I figured, I could tell if he was my father.

The problem was I had no idea when this man had lived or died. Here again, Mrs. Levin came to my aid, albeit indirectly. From the detective stories she brought me, I knew that when someone dies, an official record is created, a death certificate. If I could get that record for Kenny Pemberton, I’d know when he died. Then I could go to the library and ask for the right spool of microfiche. But where on earth would I get a death certificate?

“A what?” Ed asked, when I talked to him later that week. “What do you need a death certificate for?”

I had anticipated this response, and I was ready, even though it had taken me most of the week to figure out what I would say. “Oh, I’m doing a summer book report on local boxers, and I thought maybe I’d put in something about that boxer you mentioned a few weeks ago. What was his name?” I didn’t want to let on that it was engraved in my mind.

“Kenny Pemberton. But Steve, I’m telling you, I don’t think he was your father.”

“Oh, I know, I know, that’s not why,” I said, trying to maintain my poker face. “It’s just a book report. Everybody has to do one over the summer.”

“Well, okay, it’s not that hard,” Ed said. “You go to City Hall, go to like the Vital Records Bureau or something like that, and ask for the person’s death certificate. They’ll give it to you. They have to. It’s pretty easy.”

My plan took shape. I would somehow get to City Hall, get the death certificate, dash across the street to the library, look up the story, and find out what I wanted to know. I just needed a good excuse to be away from the house long enough to do it. Some days later, I got my chance when the Robinsons asked me to pay the electric bill the next day. To save the cost of a stamp, they paid that bill in cash at a discount department store in downtown New Bedford that took utility payments. If I ran fast and got there early, I could get to City Hall and then the library and be home in an hour.

The following morning I went through my chores as quickly and quietly as possible, careful not to wake anyone in the house. When I was finished I grabbed the envelope, tiptoeing around the creaks in the kitchen floor that I knew would signal my departure. I had my hand on the gold doorknob of the kitchen door when I was suddenly startled by the sound of Betty’s inquisitional voice, coming from her bedroom right off the kitchen: “Where are you going?”

“You told me I had to go downtown and pay the electric bill this morning.” I held my breath during the long pause that followed. If she said I could not go, I’d have to wait a month until the bill had to be paid again.

“Okay, but you better be back in an hour.”

“Yes, ma’am. But what if there’s a line?”

“There shouldn’t be no line this early in the morning. You be back here in an hour, or you know what you gonna get.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

I twisted the knob and walked out. My mouth was too dry to whistle, but I tried to amble out the door as slowly as possible, half expecting her to call me back at any moment and cancel my mission. At the stop sign on the corner near our house, I turned right onto the sidewalk along Arnold Street. Walking past the paint store, I knew I was no longer in direct line of sight from the living room. Now I just had the clock to worry about. One hour to pay the bill and find the father whom I’d waited for all these years. I shot off like a rocket, as close to a four-minute mile as an eleven-year-old in blue jeans can muster.

I ran up Arnold Street, passing the McAfees’, the Vandivers’, and other familiar houses, my feet striking the pavement in a rhythmic cadence. I was headed toward Star Store, an old jumble of a city department store well over a mile away. After several minutes I got winded and slowed down, but I didn’t dare walk.

Making it to the store ten minutes before its nine o’clock opening, I waited right in front of the dirty glass doors. Others began a line behind me. When the doors parted, I sped down the “infants” aisle, past the carriages, hampers, and baby wipes, all the way to the back left wall, where a customer service counter took municipal utility payments. Without looking at me, a young clerk with too much eye shadow on her thick, tired eyelids took the envelope. She pulled out the bill and, licking her thumb, counted the money. She counted so slowly that I began to fear that Betty had made a mistake with the payment and my plan would be ruined.

Finally, the clerk nodded, and I was free to go. I tore back through the store and out onto the street. City Hall was about three blocks away, at the corner of Main and Pleasant. Running over there, I rehearsed my story once again: I needed the death certificate for a school report I was doing.

I felt hopeful—and nervous—as I crossed the street in front of City Hall and stood before the steps. Under my feet was a large emblem with strange writing I couldn’t decipher, although I did recognize the words New Bedford. The heavy doors were an unexpected test of my physical strength. Whether a device forced them shut, perhaps to keep in the air-conditioning, or whether they were just unusually heavy, I struggled mightily to open the doors. The enormity of my task chipped away at my confidence. What if they wouldn’t give me the document?

I managed to wrench those doors open, finding myself in a small foyer. All around me there appeared to be plaques of one kind or another. An enormous painting of a whaling scene dominated the right wall. Called The Capture, it depicted several men in a whaleboat harpooning a dying sperm whale overturned on its back. In the vestibule, I found the room number for the vital records section. I headed down a long hall that I noticed was very clean. People moved around this hall, t

heir conversations echoing from the ceiling and walls. Still, they barely noticed me. I arrived at a large, high-ceilinged office with gray metal desks, yellowy light, and the languid buzz of clerks talking, file drawers opening, typewriters clacking, and phones being answered on the fifth or sixth ring. The business world had shifted to mainframes or minicomputers by 1978, but the shoe-box era would survive in this city hall for another decade. I took a deep breath and approached the long counter, standing on my tippy-toes so that I might appear as tall as possible.

A beefy, older black man with Popeye-thick forearms and a curly Afro was already standing there waiting for a document he’d ordered. He wore an orange-pocketed T-shirt and tinted shades. I recognized him immediately as a man who often walked through the neighborhood, a man the Robinsons used to call Charlie. His daughter was my classmate at Hathaway Elementary School.

“Can I help you?” a clerk asked me in that bland, all-purpose tone of officialdom.

“Yes, ma’am,” I said. “I need the death certificate for a man who used to live in New Bedford.” I swallowed hard, fighting my fear. “Um, his name was Kenny Pemberton. But I don’t know when he died.”

Conversations trailed off, file drawers stopped going in and out, and even the old Royals and electric typewriters seemed to stop clacking. Uh-oh, I thought. Two clerks looked at each other, exchanging that did-I-just-hear-what-I-think-I-just-heard expression. Charlie stared at me long and hard, but all I saw was his tinted shades. Just mentioning Kenny Pemberton’s name had propelled me into the world of big people.

The head clerk came over. “What’s a boy like you need a death certificate for?” Her tone was challenging, but it didn’t really matter: I couldn’t turn back now. I wouldn’t turn back. I had come too far.

“Well,” I said, struggling for composure, “each summer, we have to do a book report on some history of New Bedford, and I’m doing mine on local boxers.”

Now it was her turn to pause. “What school you go to young man, and what grade are you in?”

“Hathaway Elementary, ma’am, and I’m going into sixth grade.” I wondered what that had to do with anything.

“So if I called and talked to your teacher, would she tell me that you have to do this report you’re talkin’ about?”

I was amazed that she could ask such a silly question; it was summer, so of course my teacher wouldn’t be around for her to talk to. “My teacher’s Mr. Sladewski,” I said. “And school’s out, so I don’t think he’s there, but maybe he is, so you could call. Anyway, we have to do a summer report about New Bedford history.”

This was half-true. At the end of fifth grade, everyone got a summer book list, with extra credit for doing a report on any books read. But the local history part was, I admit, an embellishment.

The head clerk seemed to know that there was more to my request than I was telling, but there was no easy way for her to find out what it was. “Hold on,” she said, in a less edgy tone. “I’ll be right back.” When I again heard the droning of clerical business, I sensed that my explanation had worked.

I took a longer look at the room around me. Announcements of one kind or another were posted on the walls. On the wall behind me appeared a large map of New Bedford. To my left were rows of dark, singular shelves, and on each shelf sat a large yellow book, bigger than any I had seen. The head clerk walked over to these shelves and traced her hand along the yellow binders. Her hand came to rest on one of them, and with what seemed like Herculean effort, she heaved it down from its resting place and placed it on the desk. Her back was to me, but I could see her flipping the huge pages with enormous sweeps of her hand. My sense of wonder was interrupted a few minutes later by a very deep, gravelly voice. “Make sure ya get the story right, ya hear?” It was the man in the tinted shades.

I nodded my head vigorously in agreement.

“Look, you’re gonna hear a lot of lies about Kenny,” he said, “but don’t pay no mind. No matter what ya hear, he was a good man. He just made some bad moves. Kenny wasn’t afraid of nuthin’.” Then in a much lower voice, he muttered, as if in an aside to viewers offstage: “That was Kenny’s problem, I guess. He shoudda been afraid sometimes.”

The head clerk had come back, carrying a single sheet of paper. “Charlie Carmo, leave that boy alone,” she admonished. “He’s just doing a report for school.”

“I know, I know, Brenda,” he said. “I just wanna make sure he gets it right.” He turned back to me. “You’re gonna get it right, aren’t ya, boy?” Again, my head shook up and down. Affirmative. Yes! Charlie stared at me for another second before walking out the door. “Don’t worry about him,” the head clerk said as she slid the paper across the table. “It’s just folks around here still have a lot of feelings about Kenny.”

Years later I would find out exactly why it was so important to Charlie that I get it right.

“Yes, ma’am,” I said. “Yes, ma’am.”

Opening the City Hall doors to exit the building was somehow a bit easier than it had been pulling them apart to enter. Outside, I dared to look at the paper in my hand. My eyes scanned the sheet until I found it. Yes, I had it! The date of Kenny Pemberton’s death was August 2, 1972.

The hour was dwindling away; I’d need to hurry. I bolted across the street to the tall, old public library on Pleasant Street, barely noticing the large statue at the front entrance. Founded in 1852, the New Bedford Public Library is famous for its collection of ship logs and memorabilia about the history of whaling. An imposing granite structure, it was built in 1910 in the style of a Greek temple. Although both the library and City Hall are municipal buildings, the dignified library, with its columned portico, was as serene as the redbrick City Hall was workaday and functional.

I hurried through the library’s front door, my heart pounding. My success in getting the death certificate took my mind off Charlie’s cryptic comment. I climbed the library’s interior marble staircase to the reference section on the second floor. Walking into the room, I was as impressed as I had been on my field trip about two months earlier. Beneath the vaulted ceiling in the center was a wide, dark-mahogany desk flanked by white columns. On the walls were oil paintings of whalers in various stages of battle with the huge sea creatures. The shiny, marble-tiled floor reflected light streaming off elegant chandeliers. It was as far from the house on Arnold Street as I could get in 1978.

I got the microfiche for the New Bedford Standard-Times for July and August 1972 and set it up in the projector. The roll emitted a clicking sound as headlines flew by at warp speed, and my chest seemed to thump rhythmically with the images. As the date neared, I slowed the microfiche down. July 15 . . . July 19 . . . July 27. I was getting closer. Finally, there it was: August 2, 1972.

I scoured the headlines on the front page and local section for a mention of Pemberton, then inside those sections, then the other sections, then back to the front. Nothing. This can’t be right. There must be a mistake. I checked the death certificate to be sure I was right. It still said August 2, 1972. I went back over every page of the issue. Still nothing. I was crushed.

I glanced at the clock; I had only a few minutes left before I’d need to hurry home. I saw the librarian and thought about asking for help. I decided not to, mindful of my close call in City Hall. For the first time since I had hatched my plan to find my father, I was faced with the possibility that I wasn’t going to succeed. I put my head down on the table and began to cry.

“You okay?” asked a gentle voice. It was the librarian whom I hadn’t wanted to ask for help. Her long hair was pulled back in some kind of bun, she wore a long skirt, and her eyeglasses dangled at the end of her nose. But the main thing I noticed was her kind face. Something about the way she looked at me told me I could trust her.

“I’m doing a report on New Bedford boxers, an’ I’m trying to find an article about one of them who was—” I paused, swallowing hard, “was killed, actually. His name was Kenny Pemberton. I know the day he died,

but I can’t find any story about him in the paper for that day.”

If she didn’t recognize the local name, she intuited from my body language that whatever I wanted was very important to me. And she was compassionate enough not to ask why. “That’s okay,” she said, “I can help you.”

“Really?”

“Sure. In fact, you’re closer than you think. Remember, in a daily newspaper the stories are about things that happened the day before. So if he died August 2, you wouldn’t see anything about it until the next day. Right?”

I nodded.

“I bet if you go to August 3, you’ll find what you want.” She stepped away, indicating that she wasn’t going to do this for me.

“Thank you, ma’am. I really appreciate it.”

I was sure she was right even before I scrolled to August 3, 1972. My mind was racing with so many thoughts that I skipped over the headline at first, but a half-second later I went back, and there it was, smack-dab on the front page: “Boxer Kenny Pemberton Is Slain in Fall River.” Next to the columns of type was a small grainy photograph. I didn’t really want to study the picture until I read the story, so I half-closed one eye to blur it.

My brain tried to make sense of the cryptic phrases: “Result of an argument in the bar . . . a third man passed the pair, turned and shot . . . three or four times in the chest . . . Pemberton was dead on arrival . . . no trace . . . fleeing through backyards . . . victim had been involved in a shooting incident in New Bedford at which time a Fall River companion was shot in the right arm.” The jigsaw puzzle of police details was too hard, and so I stopped trying. But I did linger over some other words, ones easier for me to grasp: “Golden Gloves . . . middleweight boxing crown . . . Olympics trials . . . diamond class . . . one of three area boxers.”

Now my eyes returned to examine the microfiche image of “Kenneth P. Pemberton.” It showed a young man in a leather coat, his head tilted forward. He had a strong forehead and thick brow over deep-set eyes and a prominent jaw. His eyes were keenly focused on something. His mouth was half-open in an expression that held a hint of defiance—but that could also be a half smile. I stared and stared, but the shadowy image was unrevealing. Although its subject appeared African American, the photo gave no sense of skin or eye color. What struck me most about the man was his hair. It was straight and combed, in sharp contrast to my small Afro.

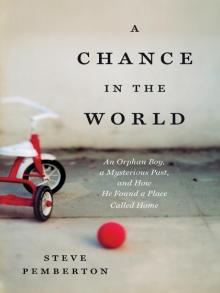

A Chance in the World

A Chance in the World